Most agree that accuracy, objectivity and honesty are fundamental principles of good journalism, principles that also underpin training at IWPR.

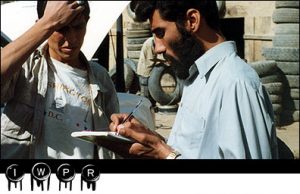

Afghan journalists are interviewing local leaders. Photo: IWPR

Journalism is as diverse as the world that it covers. Journalists who cover the news work differently than those who prepare sensational materials, write about celebrities or work as weekly columnists. The work of an American reporter is often very different from the practice of a British journalist, and they both write completely differently than their media colleagues in European countries. Styles of other continents and regions may vary even more.Однако, принимая во внимание это разнообразие, журналистские организации всего мира, тем не менее, сделали попытку упорядочить принципы профессиональной этики.

Most agree that accuracy, objectivity and honesty are fundamental principles of good journalism, principles that also underpin training at IWPR.

This chapter provides an overview of these international standards and examines the basic elements that make up the core of good journalism.

Sure, there are differences, but they more often relate to the manner of expression and emphasis. Take a look at what we offer below.

■ Caution to avoid incitement and discrimination is a hallmark of the Bosnian Press Code of Journalists.

■ Objectivity and accuracy are fundamental principles for BBC reporters.

■ The journalism canons of the Japan Association of Newspaper Publishers and Editors oblige newspapers to “make continuous efforts to ensure prosperity and a peaceful future.”

■ The Association of Journalists of Kyrgyzstan clearly defines the main thing in its code of ethics: “Journalists are required to serve the truth. The role of the media is to seek the truth. ”.

All of these codes of honor agree on what journalists should avoid:

■ libel and insult (defamation)

■ plagiarism (issuing other people’s materials for their own)

■ receiving bribes

■ making up stories (pure fabrication)

There are many different methods for applying professional approaches in journalism – how to cover war crimes, how to talk about victims and injuries, how to engage in “public journalism” or how to do “responsible reporting”; the latter is a complex and sometimes controversial topic, focusing on how to cover the conflict and how the consequences of the conflict can affect the future. Some of these topics are discussed later in this manual.

But at the heart of all this and at the basis of the contribution of the media to the development of society and the development of democracy is the coverage of events that is based on facts.

Providing reliable information in order to conduct a responsible public discussion, increasing the level of accountability of officials to the public and informing the electorate is the fundamental tasks of the media in a democratic society.

Undoubtedly, many professional codes emphasize the leading role of the media in ensuring the reliability of information.

Main elements

In almost every code of honor for journalists, there are at least three fundamental factors in journalism practice: impartiality, accuracy and honesty. They can be considered as universal standards.

Ethical criteria also emphasize the need for honesty and decency in collecting news. Many codes also include source protection as an important component in the collection of information.

- Impartiality

Most journalistic codes of honor and codes of conduct highlight “impartiality” or “independence” in describing events. But this concept may be difficult to define.

Impartiality means that reporting should not provide support for one political party, religion, people or ethnic group to the detriment of another. It allows you to provide fair information about the policies and statements of the parties and include comments that one party or group can make regarding another. But the main principle is that the journalist should not express his own opinion directly, give his comments or express personal political preferences.

Balanced journalism provides a clear distinction between what is fact and what is opinion.

Journalists must provide the votes of all parties to the event. Photo: IWPR-Georgia

In many countries, editorial offices find it difficult to survive without any financial support, and political parties, groups that influence politics, or influential businessmen with political interests are natural candidates for such support. In such cases, newspapers should at least be informed of their sources of funding so that readers can form their own opinions about their impartiality.

Responsible publications make clear distinctions between published news and editorial opinion. News appears on the front page, and editorials and opinions appear on the internal pages and are clearly marked. Some newspapers publish articles that are “analytical” and thus inevitably reflect a certain view of the journalist, clearly designated as “analysis of the news” in order to distinguish them from immediate news. In many newspapers, editorial groups involved in the production of news, and those that prepare sections of editorial articles and commentaries, work very isolated from each other and are not even allowed to communicate with each other.

In the West, many media and publications are owned by private companies, and the publication of objective materials on commercial topics requires a very delicate approach. The editorial and commercial or advertising departments are completely separate from each other.

There were times when the editor was forced to quit due to the fact that the publisher or media owner sought to influence the content of the publication. And if the editor after such an intervention remained in his place of work, then this led to the discrediting of some publications.

Often a conflict situation arises when a newspaper or a broadcasting company has material that can make it difficult for media owners or companies that order a significant amount of advertising on the pages of a newspaper or on airtime. If she publishes critical material, she may lose revenue. But if the information is hushed up, then this media becomes biased and loses its reputation.

Maintaining political objectivity is difficult for many reasons. In some countries, the media are directly pressured if they criticize the government and are considered to be strong supporters or “lackeys of foreign governments,” even if they have only tried to maintain an independent course. It is especially difficult to maintain one’s position during periods when society becomes extremely polarized.

It is difficult to be objective and for simpler reasons. The words spoken by the president of the state will undoubtedly be deemed more reliable news than the opinion of the villager, even if the leader of the state conducts open propaganda, while the peasant speaks about the neglected problems that concern the foundations of state policy.

- Точность

A journalist in Iraq listens to a recording and checks information in a notebook. Photo: IWPR-Iraq

Each journalistic code emphasizes the need for accuracy. The desire to “do it right” always prevails over speed. Those who are in a hurry but are doing the wrong thing can hardly hope for a reward.

The ability to write for a journalist is the ability to present information clearly, concisely and effectively. It should be based on solid facts; thus, the reporter needs to know how and where to find reliable information.

This means having good observation, listening skills, good basic erudition and, above all, the ability to talk with the right people when looking for reliable information.

The axiom for a journalist is that the best reporters are as good as their personal contacts. Therefore, you must learn how to improve them and how to evaluate the proposed information. This means that you need to be able to identify both reliable people (gaining their trust in you) and those who are not. An extremely difficult task is how to strike a balance between conflicting opinions about the same event.

Many journalistic organizations insist on a “two-source rule”, which means that each fact must be confirmed by two independent sources before accepting it as accurate.

Journalists need to make extensive recordings by hand or record interviews on the recorder whenever possible, to ensure that the message is as accurate as possible. Adherence to this universally recognized principle supports journalistic honesty and trust – even if it comes to spelling names correctly. Accuracy requires rigorous attention to detail, as even one minor mistake can undermine the reliability of the entire publication. These mean the need for verification and even double verification of facts and even generally recognized information.

With proper preparation of the material, it is necessary to call back the sources to make sure that what they said is written down correctly, especially if another source disputes this. This is called fact-checking, and in some reputable publications, material for the article is once again collected by a special researcher or novice journalist to confirm the accuracy of the facts, especially when it comes to a complex and especially contradictory, sensational article. Sometimes, if there is any doubt, then in order to avoid errors, the material may be delayed for another time. Failure to provide information can affect your future reputation and, in the worst case, cause serious damage, including legal action.

Accuracy is not just about facts; it has to do with context. Information harmful to the candidate before the election or the activities of the company will have serious consequences. The reader needs to know where it comes from and whether this source has biased motives.

Are there any hidden interests pushing the information that should make the journalist wary and that should be presented in such a way as to make the audience make a fair judgment? And there is a big difference in whether a consumer criticizes a product, or whether the criticism comes from a representative of a competing company producing the same product.

Many people complain that such publications are sometimes “biased”. This can be effective criticism, especially if it is clear that the journalist is pursuing his goals. Or it may just be a veiled way of saying that the article does not coincide with their point of view.

Most experienced journalists will agree that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to achieve real objectivity in presenting news. The personal experience of a journalist and his own ideas can distort the real situation. A journalist should always remember this and strive to be always objective in describing events.

First of all, any journalist relies on facts and checks the facts for their reliability. Sometimes events that cause his outrage or concern may prompt a journalist to write a good article.

But he must be honest with the search for information in order to substantiate the article, and be aware that it can lead to unexpected revelations and alarming results. The method of obtaining and describing the facts should remain objective or at least show that the journalist tried to be objective.

- Honesty

Fairness in relation to the people you interview means decency both in the collection of information and in its presentation.

Your interlocutors have the right to know what the article or program will be about; what contribution is expected from their participation; whether the radio or television interview will be live or recorded; how it can be edited. They also have the right to know whether they are being filmed and, if so, to request some changes. But honesty and decency in relations between the parties and in the presentation of the event itself should remain the most important attitude.

“A journalist should use only honest methods to receive news, photos and documents.” This means that under normal circumstances, you should introduce yourself as a journalist and refuse to use threats and use force to obtain information.

Just because you know something doesn’t mean you can use it in your article. You do not have “information” for publication until you are protected with respect to reliability, and in most cases you do not have a source confirmed “for recording” obtained honestly and openly. And only in the rarest and most extreme circumstances justified by the highest public interest can a violation of the law be deemed acceptable in order to receive information.

Honesty in the presentation consists in giving a chance to any person who you criticize to respond to those comments referred to in the same material. Someone may be upset by your article about him, but her appearance should not be a surprise to him, since a journalist should always discuss criticism with interested people before they are published. (Note: this does not mean that this person needs to read the entire article, but does mean that the essence of criticism must be explained to him.)

If you find it uncomfortable to discuss your criticism with the subject of your article, then you will still feel awkward at the publication of these materials. Expressing criticism of a person will make your message stronger, but if you include all the counterarguments and positive aspects of that person along with it, your article will be more balanced and your criticism will be more significant.

- Faithfulness and decency

The way journalists do their work and present its results — and ethical standards and practices are the basis for this — is vital to maintaining public confidence. Both written and unwritten codes of journalists speak about how important it is to play by the rules when collecting, checking and disseminating news. Given the existing difficulties and dilemmas that arise from time to time in journalistic practice, it is imperative to be aware of the boundaries of what is permissible and have guidelines for personal ethics.

In addition to accuracy and honesty, most codes emphasize truthfulness, openness and common sense when writing news reports. The need to search for information at all costs does not mean that you need to forget about decency.

For example, reporters are known for persisting in their work, but they should not tolerate insults or intimidation. Journalists should collect information openly and should not, with the exception of extreme circumstances (and with the permission of the editor), use hidden recording methods. Anyone criticized by the press should be entitled to an answer.

Journalists should avoid unauthorized interference in the lives of people suffering from injuries or shock, and must respect the individual’s right to privacy. Children and victims of sexual offenses should be treated very delicately, and the laws of many countries prohibit them from photographing their names. Journalists working for business should avoid giving information about companies in which they have a financial interest, and if they do, they should declare such interest, for example, if they have shares in these companies. Many media organizations have clear rules governing ownership of securities and trading operations by journalists.

So far, due to the complexity of ethical issues, many codes of honor and rules for journalists avoid declaring too many absolute rules. In extraordinary cases, the well-established rules of practical news journalism may be revised in the light of increased public interest. Professional codes usually clearly require journalists to never impersonate who they are not. How can a journalist expose a lie if he is dishonest himself? And yet, sometimes, as the only way to completely expose the corrupt officials, for example, it may take pretense or trick to trap such people. In these cases, it is best to consult with the editors and their colleagues, as well as follow their own ethical principles.

Another ethical rule is: never plagiarize. Each new publication, of course, is based on already published articles. But you must definitely make a reference to colleagues or even competitors from whose reports you borrow material, and you should never steal the work of other authors and pass them off as your own. Otherwise, there will be the end of your career.

When faced with an ethical dilemma, always ask yourself:

■ Is there any other way to get the same information?

■ Can you explain with good conscience your actions to those you have harmed?

■ If a similar situation arose again, would you do the same?

■ What would you do in the place of the hero of your material, and not in the place of a reporter?

■ Have you done everything to be accurate and fair?

■ Have you tried to discover all the relevant aspects of this article?

■ Are your decisions free from external and, especially, from personal influence?

- Source protection

The Code of Honor of Journalists usually attaches great importance to the protection of information sources, sometimes even in open conflict with the law. Some cite “moral obligations” not to disclose sources.

A conscientious journalist must protect his sources of information. Photo: IWPR-Afghanistan

At the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR), we consider the protection of information sources as the fundamental right of a journalist. But it is very difficult to say that such confidentiality is accepted worldwide as an international standard. Sometimes confidentiality is violated, and very often, with serious consequences for the journalist or his source. Journalists’ organizations — the International Federation of Journalists, the U.S. Journalists Protection Committee, and Paris-based Reporters Without Borders — participated in litigations in which journalists sought protection from the strong pressure (sometimes coming from repressive governments) from the purpose of disclosing source names.

In practice, reporters who promise to keep the source secret, but subsequently reveal its name, will find it very difficult in the future to gain the trust of information sources. When a source of information leakage or a political opponent makes a decisive or revealing anonymous statement in the press, officials are interested in finding out this name, as they will want to punish this person and make other people afraid to make such statements in the future.

Often the issue is limited to legal conditions. If a journalist receives confidential information from an anonymous source, the government may wish to file a lawsuit against the source, claiming that this information leak violated privacy laws.

This question relates to the very essence of the freedom of information dispute. In addition, many countries do not guarantee the right of a journalist to protect a source of information, and sometimes (for example, in the United States or Australia) in such cases, journalists may be imprisoned. Some courts are more sympathetic and rely on whether the highest public interests are respected under such protection. For example, the European Court has made some decisions that may assist journalists.

- Always pay attention to the following things:

■ Coverage of the opinions of all participants in the process. If there is a dispute, you should try to talk with “both sides,” but remember that this may not be enough. There will be “irreconcilable groups” in the conflict. But there will also be official international observers or diplomats, independent non-governmental parties and independent civilians. No one has a monopoly on the truth, but the information of the least interested person, as a rule, is the most reliable.

■ Where charges are brought against anyone, ensure that they are presented in a fair context. This means including balanced information or other important factors, in particular a fair right of reply with respect to any allegations.

■ Be open in journalistic work. You are a journalist serving the community and should be at the forefront of what you do. The clearer your understanding of what you are doing, the more success you will achieve in obtaining sensitive information from your sources.

■ Avoid conflicts of interest or situations that may provoke such conflicts. Objective journalists should not work in the public service, while pursuing their profession, occupying important posts in political parties, participating in public demonstrations, preparing a report about them or doing something else that could give the public reason to think that their activities are influenced these events.

■ Avoid financial conflicts and do not allow remuneration other than fees to be the cause of this article. Receiving payment from a source who wants to influence your description of events is completely unethical. Preparing information about a company in which a journalist has a personal interest is also unacceptable. However, it may sometimes be acceptable to take part in a dinner or, for example, a buffet reception – this should not be construed as your promise of favorable coverage and does not mean that unpleasant information will not be published. In the same way, never pay for information, except in extraordinary circumstances, which must be clearly identified in conjunction with your editor.

■ Journalists have to ask complex questions. The journalist works for the observance of the right of society to information, therefore he is responsible for the results of the investigation. But this does not mean that he should be rude and ill-bred. The BBC’s editorial guidelines say you need to be “seeker, skeptical, balanced, and apt,” but not “rude or emotionally committed to one side of the argument for anyone’s benefit.”

■ People need to know how their words or images will be used (although there are exceptions when doing secret tasks or journalistic investigations). Be honest about the basic rules of the interview and ask for permission to take photos and videos. This can be especially important when you cover an armed conflict, in which, unfortunately, the military sets its own rules. Whatever your own opinion, respect your sources of information above all else.

■ Use unnamed sources with extreme care. Sometimes journalists may use quotes from “leading diplomats” and “senior officials” or other anonymous witnesses who ask not to disclose their names. But this does not mean that you can make false allegations or, as for journalists, invent a source (another method to quickly ruin your career). If no name is provided, provide as complete a description as possible to prove that the source is trustworthy. In all cases, be open, especially with your editor, who may try to convince the source to give information not anonymously, before giving you the right to publish particularly sensitive information.

If your information is too good to be true, then perhaps this is so. Use common sense and always ask yourself:

■ Have you received your information in a reliable and moral way?

■ Have you done everything you can to be accurate, and are you able to corroborate your facts?

■ Are your decisions free from dishonest influence or prejudice?

■ Have you provided a balance and context, in particular, the right of reply and objective comments to any person criticized in your article?

■ Is there no other way to obtain information, especially in the case of an unnamed source?

■ Are your sources reliable and have you spoken to representatives of all parties involved in your publication?

■ How convincing is the material and does it make sense?

■ And most importantly: can you stand up for your material?

Video lecture by professional journalist and editor Lola Olimova (Tajikistan) on international standards in journalism:

In this section, you covered:

■ Common concepts of impartiality, accuracy and objectivity.

■ The duty of a journalist to protect sources of information.

■ General principles of codes of honor and professional activities.

■ Some points to keep in mind when reporting and writing articles.

Exercise 1

The police tell you “not for the record” that they are going to arrest a local businessman who has a good reputation for his charitable and social activities. Police say they are checking allegations of fraud and bribery. It is already late evening, and there are no official documents.

You call a businessman who confirms that he is aware of the allegations and that he is awaiting arrest the next day. He refuses to give a direct answer about the prosecution. He asks you to postpone the publication for one day so that he can tell his family. He says that he will “take care of you” if you can delay the publication of the article.

■ What is the ethical dilemma?

■ Are there other practical problems in this case?

■ Should you discuss this with anyone?

■ Do you need more information?

■ Should you prepare information for print?

■ How would you write a message based on the small number of facts listed above, and what do you need to properly expand the message?

Exercise 2

You made material about a war crime and published important information that drew public opinion to the crime. In doing this, you firmly adhered to all the classical ethical rules of journalism: showed respect for your sources, carefully kept your notes, publishing only what you can confirm.

A few years later, an international tribunal calls you to testify. Your notebooks should also be presented in court. You are called upon to break the oath of the journalist and give the names of the sources and other information that you, as a journalist, did not publish at the time.

Do you participate in a tribunal to support a charge of alleged war crimes? Or do you refuse, even personally risking, defending a code of honor for journalists?

Also refer to the Project on the excellent quality of journalism:

For a list and texts of several codes of journalism:

http://www.asne.org/index.cfm?id

http://www.poynter.org/column.asp?id-32&aid=16997

http://www.nytco.com/pdf/NYT_Ethical_Journalism_042904.pdf

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.